What is Data? Building Blocks to Model Our World

Let’s talk about the definition of data. After all, it fuels the engine of modern enterprises and its abundance is revolutionizing how decisions are made across a variety of domains. But what is data really?

Most people today, whether trained as data practitioners or not, have an understanding of what is meant when we talk about “an abundance of data”. It seems as though everyone has some sort of social media profile – regardless of their age or background – and we willingly (or maybe naively) surrender portions of our personal information and privacy when we accept cookies on websites that track our browsing behavior, or opt to share our information across our various profiles and devices to have a seamless experience. Think: logging into accounts using Google email addresses, connecting to our Nest thermostat’s, etc. etc.

Contents

So… What is Data?

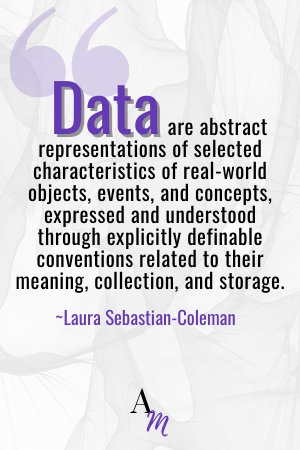

Perhaps my favorite definition of data is given by Laura Sebastian-Coleman in her book Measuring Data Quality for Ongoing Improvement. She is a scholar of the English language, and you can see how precisely she uses nuances of language to explore the meaning of the word “data”. She says the following:

“Data are abstract representations of selected characteristics of real-world objects, events, and concepts, expressed and understood through explicitly definable conventions related to their meaning, collection, and storage.”

Laura Sebastian-Coleman

She then proceeds to talk about four different ways that data is conceived: Data as Representation, Data as Facts, Data as a Product, and Data as Input to Analyses.

Data As Representation

When considering Data as Representation, Sebastian-Coleman discusses semiotics – the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation. I will boil this discussion down into three main points.

- Data are abstract and stand for things other than themselves.

- Data represent selected characteristics of objects, events and concepts. In this sense, data are models.

- There are infinitely-many ways that a thing can be represented. This implies that we create data – it does not just exist – and in its creation, we make choices about data – we get to define measures, precision, categorical values – this is where some of the “art / creativity” of analytics and data science comes into play, as well as some of the ethical considerations in the space. We make choices about the data that we create.

So that’s Data as Representation – the idea that data are abstractions of the world around us.

Data As Facts

Next, when we consider Data as Facts we are challenged to acknowledge the importance of context. If I advance the number 36.158 as an example of data, this number alone does not have meaning. Rather it is the context that ‘this is my age as of today when I am writing this post’ which constitutes a statement of fact.

The context or data that describes the data and transforms it into fact is called metadata. I often say that metadata is data about data, but Sebastian-Coleman goes beyond this elementary definition and says that “Metadata explain how data represents the world”.

Data As a Product

A third way that data is discussed is as a product. When you think about a product that is created – let’s say a smart phone – we are concerned with the process by which that smart phone is created, how much time it takes to make, what resources go into it, how the manufacturing process can be documented and replicated, etc. We want to be efficient and we want to maximize our potential profit when we go to market.

When considering Data as a Product, we are called to think of data as being created with intention versus thinking of data being created as a by-product of a process (being created without intention).

As a product, the overall life-cycle of the data is meaningful – this means that we must understand and document the processes that produce it, measure it against specifications, and address data quality issues at their root causes.

Data as Input to Analyses

Finally, let’s discuss Data as Input to Analyses. In this setting, we must evaluate the validity and appropriateness of data to solve a problem or to create new knowledge.

This formulation is perhaps easily stated, but is quite complex – especially when considered with data as representation. Often, we, as data practitioners, are called to lend our expertise into sourcing data and evaluating ‘the art of the possible’ to gain some type of insight or efficient path to a decision.

In its raw form, data are very rarely (if ever!) ready, appropriate, or valid. We work our magic to get data ready to be used as an input into analysis by merging, formatting, creating features, modeling, and the like. This makes the data more ready, appropriate, and valid, but can also introduce complexities (like bias, incomplete stories, etc.).

Data as an Output of an Analysis?

This does not mean that the work that we produce is not useful – quite the contrary – like I said, we work magic. I do believe, however, that it is important that we are ALWAYS(!) clear about our sources and limitations. This means too that we are responsible for helping others to understand and use our data appropriately as well.

In that sense, I’d like to extend the idea of data as an input into analyses to also include data as an output of an analysis – and the (ethical) responsibility that accompanies it.

Conclusion: Pondering How We Model Our World

So, that’s a brief discussion of what data is, and different formulations used to understand it: Data as Representation, Data as Facts, Data as a Product, and Data as Input to Analyses.

Think about this as you make sense of the world around you!

What else might you add to our understanding of data? Let me know in the comments below.

Leave a Reply